⚠Content Warning: Sexual Violence, Sexual Coercion, Child Sexual Assault, Rape Apologia, Pedophilia (Non-Graphic)

This essay is one of a two-part series. Read Part II here.

Table of Contents:

- On Strange Bedfellows

- “Rape is Not About Sex, Rape is About Power”

- Final Thoughts: Rape as the Sexualization of Power, or Power as the Asexualization of Rape?

On Strange Bedfellows

You have most likely heard someone assert that, “rape is not sex, rape is power.” Or the somewhat less reductive: “rape is not about sex, rape is about power,” or “rape is not about desire, it is about power,” or any other variation on the classic anti-rape slogan.

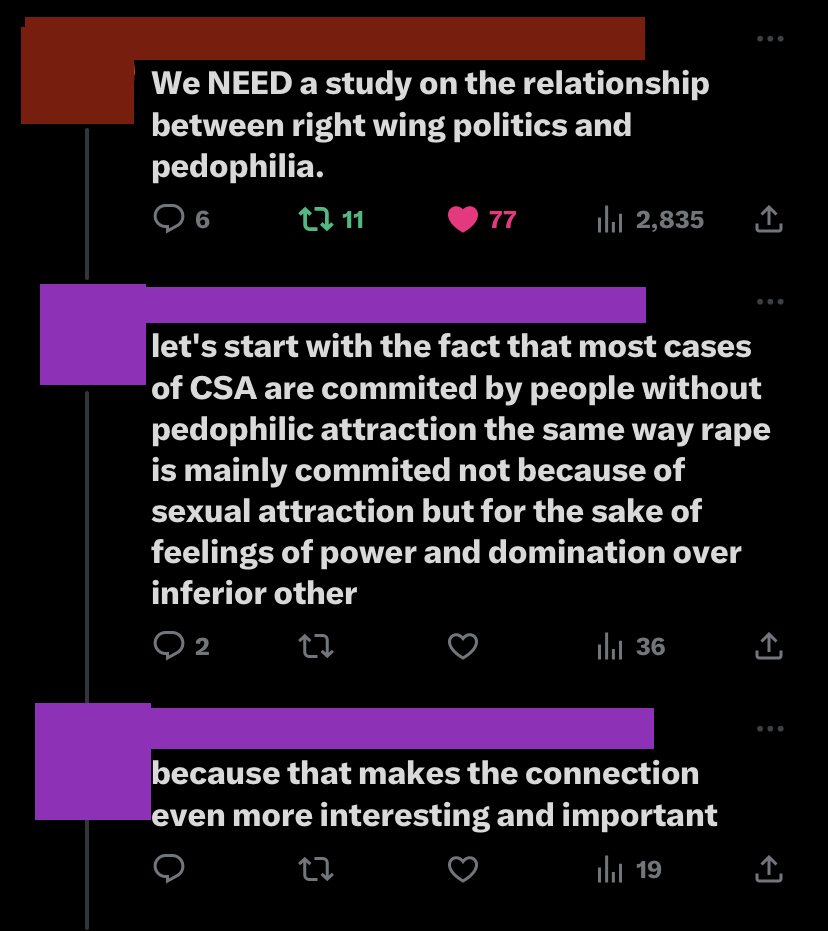

I have to admit these slogans have always rubbed me the wrong way, for reasons I hope will become clear soon. However, more recently, I have repeatedly seen them deployed in a number of troubling ways, most especially in combination with another, seemingly similar assertion: “most people who commit sexual abuse of a child are not ‘(true) pedophiles,’—not people who have ‘pedophilic attraction’—rather, sexual abuse of children is ‘about power.’” For example, take the following interaction:

Although at first this may seem like a perfectly reasonable parallel, these two propositions have strikingly different points of origin and frameworks behind them. Slogans like “rape is not about sex, rape is about power,” come from anti-rape activism, most of the time at least downstream from radical anti-rape feminism, but the claim that “most perpetrators of child sexual abuse are not (so-called) true pedophiles/most perpetrators of sexual violence against children are not sexually attracted to children,” comes directly from the often deeply trans-antagonistic field of academic sexology, a field profoundly hostile to feminism per se, especially transfeminism, and in many ways constructed as a systematic, academically legitimized “rebuttal” to feminist political knowledge of sexual violence. In fact, this claim in particular, about the distinction between “true pedophiles” and “sexual abusers” acting opportunistically, comes directly 1 from the highly idiosyncratic, widely discredited psychosexual “typologies” of Michael Seto, James Cantor, Ray Blanchard, and other sexologists associated with the International Academy of Sex Researchers and the Clarke Institute of Mental Health. Although it should be observed that in the original context, the claim was not usually that sexual abuse of children is about power, but rather that it is a “crime of opportunity.”2 Somehow, this seems to have been hybridized with the feminist slogan.

The whole story of academic sexology and its long history of association with the anti-feminist movement, transphobia, rape and sexual abuse3 apologia, links to the Father’s Rights and Men’s Rights movements, associations with organizations and individuals that provide legal aid to adults (mostly cis men) accused of sexual abuse, and its many curious links to the so-called “Man-Boy Love Movement,”4 is far beyond the scope of this essay. As is any detailed analysis of the problems with the “paraphilia” framework produced within this psychosexual approach, which would require an entire other essay. Even the specific claim itself that caught my attention: “most perpetrators of sexual violence against children are not sexually attracted to children” deserves its own full length analysis. Hopefully I will be able to write further analyses on these subjects in the near future. For now, suffice to say:

1. There are many compelling reasons to be extremely suspicious, especially as anarchists, of anything this particular academic milieu says about sexual violence, power, and so-called “pedophilia.”

2. Sexology, because it attempts to divorce sexual violence from structural power and oppression and attribute sexual violence, coercion, and abuse to pathologies of individual psychology or to mere “crimes of opportunity,” is inherently antagonistic to any feminist critique of rape culture.

Just keep these things in the back of your mind next time you see this claim floating around.

And yet, I keep seeing these two assertions from categorically antagonistic points of view expressed side by side: one expressing the knowledge-claims of scientifically dubious, trans-antagonistic, generally feminism-hostile sexology and the other expressing the knowledge-claims of sex-positive feminism and anti-rape activism. How could “rape is about power,” a classic feminist critique of rape culture come to be routinely deployed in such a strange, contradictory context? Even more striking, I have repeatedly witnessed self-identified “Minor Attracted Persons,”—people who self-identify as pedophiles—use this very claim in attempts to supplant feminist critiques of rape culture entirely, by replacing them with the point of view of clinical, pathological sexology.

The scope of this essay is limited to examining and articulating the feminist critique itself, and the ways I think it has been reduced over time into something that can be interpreted as compatible with ideological frameworks fundamentally antagonistic to feminism. Specifically, addressing the way it seems to be expressed in assertions like the above.

“Rape is Not About Sex, Rape is About Power”

First, the slogan “rape is about power” is derived from a specific rebuttal to the myth that people (namely, cis men) commit rape because they are overwhelmed by sexual desire, by “temptation,” or even by the beauty of the victim themself, which I will discuss below.

Therefore, the feminist critique could be more accurately phrased:

“rape is not about being overwhelmed by desire, it is about the exercise of power.”

Before continuing, I should explain that there is no singular monolithic “feminism,” but many feminisms, and they don’t always agree. While it’s true that some feminists, (e.g., Susan Brownmiller and noted TERF and self-described pederast Germaine Greer,) especially (but not exclusively) liberal sex-positive feminists and libertarian choice feminists beginning in the ’80s, have taken the more literal route of asserting that rape is solely an act of violence and not sexual, it’s also true that they have been heavily criticized by other feminists, including but not limited to Marxist feminists, socialist feminists, Black and Third World feminists, transfeminists, and yes, anarchist feminists like ourselves.5 Besides failing to answer the obvious question, “if it is solely about violence or power and has nothing to do with sex, why didn’t he just hit her?” (non-sexual physical violence is, after all, the predominant means by which adult cis men assert power over other adult cis men), it disavows the unavoidable reality that rape victims—of whom the gender-marginalized and children make up the vast majority—overwhelmingly (if not necessarily always) experience rape as sexual. And rapists, likewise, often (if not necessarily always) experience rape as sexual—as the pursuit of sexual gratification—as much as they experience it as power (and they may not experience it as power at all, as we shall see.) For example, Susan Brownmiller falls into the camp that argues “rape is not about sex” and comes from a strictly bioessentialist point of view, according to which the so-called “biological sexes” of human anatomy and the corresponding (hetero)sexual act are ontologically pre-social or “primal.” Sex and sexuality therefore exist outside the social world in which power relations come to exist; power is social, sex is anatomical, therefore rape (being about power) is social, but sex(uality) is biological and pre-social. (She contradicts herself somewhat, however, by locating the “structural capacity to rape” and “structural vulnerability to rape” in the “primal” reality of human anatomy, a view now popular among TERFs.)6 Certainly not all of the feminists who took this view were bioessentialists—many were not, and most would have regarded themselves as welcoming to “transsexuals” as was the terminology of the time—but you may be reminded of the popular liberal claim that “gender is social but sex is biological,” and with good reason. In fact it is something like this view, I suspect, that underlies popular progressive adoption of “rape is not about sex”; it is a wish to locate “sex” and “sexuality” or “sexual desire” outside the world of the social and hence outside power, outside gender, and indeed outside critique.

On the other side, many critics of what they called the “desexualization of rape,” such as Monique Plaza, Winifred Woodhull, and Teresa de Lauretis, took a strongly social constructionist point of view, understanding not merely gender and power but even so-called “biological sex” and “sexuality” to be social, and therefore implicated in the institution and ideology of patriarchal power. They argued that taking rape out of the realm of “the sexual” and placing it exclusively in the realm of “the violent,” allows one to be against it without having to interrogate the social institution of (hetero)sexuality and its normative codes. To claim that rape is “not sex” defangs the critique of cisheteronormativity. On this, at least, although certainly not everything,7 I agree with the critics. I would argue that this split, which played out especially through the era of the feminist sex wars of the ’80s and ’90s,8 is the point at which the critique expressed in “rape is about power” already begins to lose its force, and the seeds of its eventual co-opting by proponents of explicitly anti-feminist frames like sexology were planted.9

Nevertheless, what both the “rape is not sex” feminists and their critics agreed on was that the slogan and associated arguments originate as a counter to the patriarchal myth I described above: that rape is caused by the rapist being overwhelmed by desire. And they all certainly agreed on the specific critique of the myth itself: “rape is not about being overwhelmed by desire; rape is about [the exercise of] power.” While some came to the conclusion that rape was “not sex” by artificially separating sex from power, others maintained that, “[i]nstead of sidestepping the problem of sex’s relation to power by divorcing one from the other in our minds, we need to analyze the social mechanisms, including language and conceptual structures, that bind the two together in our culture.”10

This general agreement points to the fact that this critique stems at least originally from the robust network of feminisms that treats sexuality, desire, and power as inseparably intertwined in the operation and production of patriarchy. Importantly, the exercise of power is not always about “feeling” powerful and dominating. Very often the exercise of power is subjectively felt by the person enacting it as being functionally “power-neutral.” Practices of power are often taken for granted as naturally occurring or just the way things are, not as an actively felt experience of domination. A person feeling powerful, feeling an active sense of personal power, is not synonymous with a person actually exercising power upon the body of others. Both in the sense that a person can feel powerful while they have no access to material power and in the sense that a person can feel powerless while actively exercising power.

Consider BDSM: ideally, BDSM involves the dominant party feeling a sense of power while not actually exercising any material coercive control over the submissive party. Feeling power and enacting or exercising power are not the same thing.11

Because, straightforwardly, power is not a feeling.

Power is the capacity to enact or impose your will. Especially the capacity to impose your will upon others.

The original feminist critique emerged in the context of a specific ideological struggle about the nature of sexuality, desire, and sexual violence. It is a counterargument to a claim about the nature of rape that goes something like this: sexual desire can be so overwhelming that a person (usually a cis man, implicitly or explicitly, in the mindset of the rape apologist) can be overcome by desire and lose control of themselves. Rape, in this view, is not an assertion of power but the result of a loss of power on the part of the rapist, a loss of control over their own body. This claim inverts the reality of rape in order to frame the aggressor as not an aggressor at all but, at worst, a man who succumbed to his weakness.

The point was to reject the notion that rapists are powerless against their own desires, to insist that rapists hold full agency in their actions and that sexual violence is not merely an individual “mistake” or “loss of control,” but a manifestation and practice of structural and systemic power. Importantly, the crucial role of rape as an operative mechanism of systemic and structural oppression means that rape cannot be solely about an individual rapist’s personal experience of power, even though for some individual rapists, a personal experience of feeling dominant and powerful may be a component of their motivations. This means that regardless of whether the individual rapist feels a sense of power domination, (which they may or may not) the act of committing sexual assault is (1) an exercise of sexual, gendered and embodied power, (2) made possible through systemic forms of power that encourage and permit sexual violence along gendered and sexualized lines, and (3) a social operative mechanism of oppression.

Closely related to the idea that a rapist is simply “overcome by desire” is the particular style of thinking according to which being sexually attracted to someone or sexually desiring them gives them power over you. Tropes like the femme fatale, the notion of “feminine wiles,” and broadly, the idea that subaltern genders (including children!) can wield their “desirability” to control and have power over the helpless targets who desire them (again, implicitly cis men, understood as the default desiring subject.) In this context, sexual assault has sometimes been framed as a means of taking that power “back” from the desirable person, or at minimum as a consequence of the desirable person’s “power of desirability.”

We find this rationale deployed as abuse apologia in the context of sexualities and sexual acts which are at least ostensibly socially proscribed: a man who is in a “relationship” with an adolescent or child is sometimes framed by apologists as being essentially at the child’s mercy, the child is “the one who holds the real power in this relationship,” because they, as an object of desire, can easily wield their desirability to control their “lover.” This line of thinking obviously turns up in consciously apologist texts about such “relationships,”12 but also turns up in the ostensibly objective and analytic worldviews of liberal academic historians, anthropologists, sociologists, and so on, who would likely otherwise consider themselves fervently opposed to “sexual abuse” and would even very likely be offended by the comparison.13 The point is that it is a normative style of thinking, not confined to people who consciously advocate for inegalitarian “relationships” of this kind, but widespread and often unconscious. This is the nature of rape culture; its ideology is the norm of society, not the outlier. The putative power wielded by the object of desire is derived from their status as the “gatekeeper” of the sex the desiring-subject wants so badly. They can refuse or reward, they can tempt and tease, and so on, but ultimately the “power” to decide if sex is going to happen, if they are going to “give” the desiring-subject sex, if they are going to save him from his suffering, is allegedly entirely in their hands.

In this worldview, it is the desiring-subject’s personal strength to resist overwhelming desire that prevents them from committing sexual assault. With this in mind, let us reconsider the standard sexologist claim that “…sexual offending [against children] is expected when a motivation to seek sexual gratification is combined with low self-control and opportunity“14 [Emphasis mine], with a view of the context we have just discussed. Since sexologists argue that most sexual abusers are not so-called “true pedophiles,” (not fixedly attracted to children)15 we can infer that the “opportunity” somehow directs sexual desire (the “motivation to seek sexual gratification”) toward the victim. In other words, “opportunity” here implicitly means “temptation,” not merely random circumstances: it is the opportunity itself that actually produces desire toward a specific object. This framework, that sexual abuse “is expected” when a desiring-subject (a subject with “motivation to seek sexual gratification”) is overwhelmed (because of low self-control) by temptation (opportunity), is the exact inverse of the feminist critique in all its forms, even the slogan “rape is not about sex, rape is about power,” which I have criticized for opening the door to co-optation. It exactly reproduces the very myth the slogan came to exist as a rebuttal against.

But there is a quiet part to this myth, too: if the object of desire promises sex and then withholds, wields their “desirability” to “control” the desiring-subject but never intends to reward his “obedience” by granting sexual access to their body, then if the desiring-subject should be overcome with desire, lose control, and take what is being withheld, then it is the rapist who is framed as taking power back from the object of their desire. The desirer’s actions are framed as essentially understandable (because they have been a “victim” of “cruel” and “withholding” control) and the rape is even implicitly seen as perhaps deserved (after all, the manipulative desire-object must have known they were playing with fire, right?) Moreover, I draw your attention to the words “overcome” and “overwhelmed.” These words, when used to frame sexual assault as a product of being “overwhelmed by desire” position the rapist as the one who is actually losing power through the very act of sexual assault, while framing rape as the expression of the victim’s power to entice and incite. Paradoxically, rape becomes the means by which a helpless desirer takes power back from the desire-object who controls them by inciting desire and a moment of individual weakness during which the rapist loses all power over their own body and is helplessly controlled by the desire inspired by the victim.

The feminist critique rejects this whole worldview by stating that sexual assault is a sexual practice of exercising power. The feminist framework sees sexual practices as a key site for the production of gender roles, “sexed bodies” (the notion that bodies become “sexed” or imbued with “sexual difference” through discourse and through embodied, gender-reifying sexual practices), and power itself.

The critique was about rejecting the false dichotomy between sexual practice and exercise of patriarchal power. It was never supposed to be about positing a mutually exclusive boundary between sexuality/desire, and the exercises of power. It was quite literally the opposite. It was about recognizing that rape is the both the ultimate expression of the patriarchal sexualization of power AND the ultimate means of imbuing bodies, sexuality, and desires with hierarchical, power-stratified meanings.

Rape, in this feminist analysis, is the invention of patriarchal gender.

It is the archetype and paradigm of heterosexuality as a hegemonic ideology (which, it must be made very clear, does NOT mean “all hetero sex is rape.” That is a strawman, which I don’t have space to explore here, but it needs to be preempted anyway. Hegemonic sexual ideologies are not the same as sexual identities, and although sexuality is socially constructed, individuals have agency to operate both within and against the constraints of socially constructed institutions in complex ways.)

Phenomena like prison rape (which is, in my experience, typically brought up as an example of cishetero men sexually assaulting other men as a means of asserting power over them, although prison rape is certainly not limited to the practices of incarcerated cis men) are not proof of the absence of sexuality in rape, nor that sexual violence is “not about sex,” they are instead very blunt practices of the sexualization of power, and the practice of sex as a key site for the production of power. The victim of a prison rape is understood as “dominated” not just because his rapist has asserted power over him—which he could just as easily have done by physically assaulting or injuring him—but because he has been subjugated into the sexual position of a woman or a child within a patriarchal sexual economy of power, gender, desire, domination, and subordination. It is not just some abstract form of gender-neutral, sexuality-neutral “power,” but a sexual practice of power that coercively genders the subject and sexes the body, through the imposition of sex on the body. Prison rape doesn’t prove that sexuality and power are categorically separate, but literally the opposite: it shows that (quite specifically gendered) power is exercised and constructed through sexual practices enacted through and upon the body.

The feminist critique was a rebuttal to the ways power was framed as playing a role in sexual violence. It was a rebuttal both to the false dichotomy that presents sex and desire as inherently outside power and to the notion that power is generated by desirability.

To take that feminist analysis, which so crucially depends on an understanding of sexuality, desire, and power as intertwined and co-constitutive, and warp it into “rape is not sex, rape is sexless, separate from sexuality per se, and only about ‘feeling powerful’” actually undermines the original point!

Treating sexuality, desire, and power as mutually exclusive, the presence of power as implying the absence of sexuality or desire, is quite literally reverting right back to the exact false dichotomy the critique exists to refute in the first place. The patriarchal thinking being refuted imagines that the presence of sexual desire voids the exercise of power: the rapist is rendered powerless by sexuality and desire. Ipso facto, a desiring-subject can only exercise power over the bodies of others if he does not sexually desire them. But what I have seen time and time again, is this one-time feminist critique being turned on its head and used to return to that exact false dichotomy, just approaching from the other side: to deny the sexualization of the exercise of power within patriarchy.

Final Thoughts: Rape as the Sexualization of Power, or Power as the Asexualization of Rape?

There is a curious discursive tendency forming here too, in my opinion, although this is rarely ever stated as a consciously held belief: rape comes to be framed (usually unintentionally) as an inherently asexual practice of power. Power itself is framed as the inverse and mutually exclusive opposite of “sexual,” which is, by definition, in the domain of the asexual. Power becomes discursively situated safely outside allonormative practices of compulsory sexuality, as the “Other” to allosexuality and to allosexual ways of desiring, ways of relating to desire: power, in other words, is being discursively asexualized, and by extension, then rape, too, as “power but not sex,” is asexualized.

This is, in fact, not actually new. There is a long tradition in, you guessed it, academic sexology and psychiatry, (among other disciplines), of (1) constructing asexuality as pathological “repression” or arrested development, as inherently unhealthy, abnormal, and disordered, and thus as tending to produce unhealthy, abnormal, and disordered sexual behaviors, including sexual violence against adults and children, and (2) distancing sexual violence as far as possible from sexual desire (especially the desires of cis adult men), with sexual violence framed instead as a product of a diseased mind, alien to and outside normative modes of desiring. (Such as, for example, an unhealthy, disordered, repressed sexuality!) In particular, there is a strong historical precedent for framing sexual violence against children as a product of arrested psychosexual development in which an adult is stuck at the “infantile,” undeveloped stage of sexuality, including the purported stages of “childhood asexuality” and “adolescent homosexuality.” For more on this fascinating history, I recommend reading “Crimes Against Children: sexual violence and legal culture in New York City, 1880-1960” by Stephen Robertson and “Refusing Compulsory Sexuality” by Sherronda J. Brown, but I won’t go further into the whole history right now. I mention this mainly to gesture at some possible clues about the kind of biases and presuppositions about sex and (a)sexuality that have played a role in the sexology framework coming to be seen as compatible with (a somewhat reductive, oversimplified understanding of) the feminist critique of rape-as-power.

It should be noted, finally, that to insist that “rape is about ‘feeling‘ powerful and dominating” is once again to actually reinforce the notion that rape is a product of individual psychology (the view preferred by the pathologizing framework of sexology) rather than systemic structural power.

I want to make it clear that when I allude to finding the claims of sexology problematic or suspicious, I am not at all rejecting the notion that practices of power lie at the heart of sexual violence against children. Instead, I am rejecting the notion that sexual abuse of children is always about feeling powerful, about having a subjective experience of power, or that sexual abuse of children is chiefly opportunistic and unrelated to having sexual desires directed at children. I am rejecting the false dichotomy between those who supposedly have an intrinsic or pathological “attraction to children” that is beyond their control, and those who sexually abuse children purely out of “opportunism” but supposedly have no “attraction to children,” the notion that “pedophilia” constitutes an overwhelming urge or desire which the desiring-subject is powerless to overcome, even if they are strong enough to “resist” the urge to “offend.” This set of ideas, if it is not clear, seems to unavoidably entail the view that sexual desires are overwhelming, natural, pre-social or non-social forces that exist outside of power, and that a desiring-subject is either strong enough to resist or becomes overwhelmed by them—the same view discussed above as part of the network of patriarchal ways of thinking that conspire to excuse and justify rape culture. Someday soon I hope I will be able to write out a more thorough critique.

For now: it is true that any individual rapist (whether their victim is an adult or a child) may or may not be motivated by a personal pursuit of subjective feelings of power over the inferior victim, but this is not what is meant by the feminist analysis that rape is about power.

What is meant is that rape is the material, embodied, exercise of power. Rape is an operative mechanism of oppression, at the interpersonal and the structural level. That power is not purely individualistic or personally felt, although it (obviously) functions at the level of interpersonal power too: instead, rape is a function of structural and systemic power. Child sexual abuse is no different: it is a function of structural and systemic power. And so is sexual desire toward children. These things cannot be meaningfully disentangled in the way sexologists attempt to do.

Pestering your partner over and over again for sex, even after they have said no? That is an embodied, gendered and sexual exercise of power, even though it is unlikely that many people who do this think about it as personally empowering. Many who do this very likely think their partner is “the one with the real power,” since their partner is “gatekeeping” the sex they so badly desire.

The person doing such a thing is likely to be personally motivated primarily by sexual desire, but what they are doing is nonetheless sexual coercion—the application of coercive power—regardless of how they subjectively feel about their motivations. They are choosing to act in a way that expresses their sense of entitlement to de facto ownership over the body of the other. They are not choosing to engage in this coercive practice because they are just so overwhelmed by the power of their desire and can’t help themselves, nor is sexual desire entirely unrelated to the particular sense of corporeal sexual ownership they are expressing. What they are doing is attempting to exercise power over their partner’s body, attempting to overrule their partner’s consent, attempting to assert their right to have their sexual desires met through the subordination of the other’s autonomy to their own desires. They are exercising the capacity to impose their will.

And that is the point of the feminist critique.

– narcissus

Download:

PDF (Screen reading)

Read Part II

- EDIT: a minor correction is in order. It has since come to my attention that this claim originates further back in the history of sexology, at least to the time of John Money and Richard Green in the 1960s, but probably earlier, stemming from the development of the psychosexual/pathological category of “pedophile” to begin with. Sexologists working in the areas of “sexual typologies” and the paraphilia model, such as Seto, Cantor, Blanchard, J. Michael Bailey, Kenneth Zucker, and others, are drawing heavily on that same earlier work, and are indeed colleagues and collaborators with sexologists like Richard Green, who founded the journal Archives of Sexual Behavior, of which Kenneth Zucker is now editor-in-chief. Much of the usually-cited contemporary “evidence” for this claim is, however, directly derived from the works of Seto, Cantor, Blanchard, and their associates. See, e.g., Blanchard citing Michael Seto as an authoritative source on this claim. ↵

- For example, see Seto, Michael (2018) Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children: Theory, Assessment, and Intervention, 2nd Ed., passim ↵

- Some of this history is reviewed reasonably well in Goode, Sarah D. (2011). Paedophiles in Society: Reflecting on Sexuality, Abuse and Hope. But some scrutiny and cautiousness should be exercised in reading this source, which has some weaknesses in its analysis, approach, and its use of sources. ↵

- As just one example, sexologists like Theo Sandfort, (who is associated with the editorial board of the Archives of Sexual Behavior, the journal controlled by the International Academy of Sex Researchers,) have repeatedly co-authored academic works on “Man-Boy Love” with “Pedophile Emancipationist” political activists like Edward Brongersma, and even sat on the editorial board of pro-“pedophilia” pseudoacademic journals like Paidika: the Journal of Pedophilia. Brongersma and other “Man-Boy Love” activists continue to be cited as a credible source by contemporary sexologists like Michael Seto. ↵

- For some examples of such critiques, see Monique Plaza’s excellent and scathing rebuttal to Foucault in Plaza, M. (1980). Our damages and their compensation. Feminist Perspectives on The Past and Present Advisory Editorial Board, 183., and Lauretis, T. D. (1989). The violence of rhetoric: Considerations on gender and Representation’. The Violence of Representation: Literature and the violence of Literature, Routledge, London. ↵

- For a critique of Brownmiller, see Woodhull, W. (1988). Sexuality, power, and the question of rape. Feminism and Foucault: Reflections on resistance, 167-76. ↵

- Among the most outspoken critics is Catherine MacKinnon. Her social constructionist criticism of “rape is not sex” in Toward a Feminist Theory of the State is cogent and insightful, but the flaws in her broader analysis become painfully clear in her now infamous carceral and statist activism against pornography. ↵

- For a succinct overview of the early “sex wars” written from the then-contemporary perspective, see Ferguson, A. (1984). Sex war: The debate between radical and libertarian feminists. Signs: journal of women in culture and society, 10(1), 106-112. ↵

- In fact, Gayle Rubin’s “charmed circle” theory, which came to be very influential in the following years, was strongly influenced by academic liberal sexology. Rubin, drawing from sexology on the one hand and Foucault on the other, (extremely strange bedfellows to anyone familiar with Foucault’s acidic views on the “sexual sciences,”) argued that “sexuality” and “gender” had to be separated into different realms of analysis, and therefore “gender oppression” separated from “sexual oppression.” This is inevitably a move toward the “gender is social, but sex is biological,” liberal frame of today that is heavily critiqued by transfeminists—arguably the foundational move in that direction. There is certainly much to be said about Rubin’s influence on popular feminism and the influence she drew from sexology, but it is beyond the scope of this essay. For a critique of both Rubin and MacKinnon, see Valverde, M. (1989). Beyond gender dangers and private pleasures: Theory and ethics in the sex debates. Feminist Studies, 15(2), 237-254. ↵

- Woodhull, (1988). Sexuality, power, and the question of rape, 171. ↵

- BDSM was a point of contention in the feminist sex wars precisely because of feminists’ contending theories of power; on this topic, I take the side of the sex-positive feminists, but again, a full critique of the sex wars’ battles lines on BDSM is beyond the scope of this essay. ↵

- For example, again see quotes like the following from sexologist Theo Sandfort’s (1985) Boy’s On Their Contacts with Men: a Study of Sexually Expressed Friendships: “…it can be seen that the boy realized he could withhold sex from his partner and so use it as a power tool.” (p. 95, emphasis mine) ↵

- For example, see quotes like the following from classical archeologist Judith Barringer’s The Hunt in Ancient Greece (2001), describing the Ancient Athenian practice of pederasty as “…a vacillating exchange of power between the older erastês, who holds social status, and the erômenos, who, by virtue of the desire that he inspires in the erastês, possesses power.” (p. 70, emphasis mine) ↵

- Seto, Michael. (2018). “Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children: Theory, Assessment, and Intervention.” 2nd Ed. p. 86 ↵

- We technically agree, although for very different reasons—we reject the paraphilia model entirely and along with it the notion that there is a set of “chronophilias,” including pedophilia, ephebophilia, and so on, that are allegedly biologically innate to those assigned male at birth, benign sexual variations, or deviancies produced by psychosexual abnormality (all three claims have been made by sexologists). “True pedophiles” do not exist in the commonly understood sense, but are socially constructed, because sexuality and desire are both social, not biological or pre-social. For a better analysis of how sexual desires become directed toward children, see Liddle, A. M. (1993). Gender, desire and child sexual abuse: Accounting for the male majority. Theory, Culture & Society, 10(4), 103-126. ↵